An excerpt from the interview:

John Madera: Would you talk more about this “webbing” that connects everything with everything, about reality as a text?

Lance Olsen: Maybe our real job as writers, I sometimes want to say, perhaps even as human beings (with the accent on the plural noun), is to continuously learn to pay attention to the world we move through. Yet the world—which is to say how we’re wired—plots against us. Our default mode of being often wants to be the habitual, which is to say the unexamined, which is to say our default mode of being-there wants to be not-being-there.

What’s astonishing and invigorating for me about what I consider difficult art—a sentence, say, in Ben Marcus’s Age of Wire and String or Gary Lutz’s Stories in the Worst Way; the architectonics of David Lynch’s Lost Highway; the complexity of any two seconds of a text-film by Young-Hai Chang or corner of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights—is that it seeks to return us through challenge to attention, which is to say contemplation.

Another way of putting this is to move from the aesthetic to the existential and think about what your answer might be to Annie Dillard’s rattling riddle: “Assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?”

In other words—and this eases us toward a tentative answer to your second question about reality’s textuality—paying attention is a continuous condition of learning (and unlearning) how to read. The world is nothing if not a text composed of a multitude of texts (just as each of us is nothing if not a text composed of a multitude of texts) we try to make sense of, narrate, and, as Derrida reminds us, there is nothing outside the text.

But here’s the deep-structure dilemma: humans are by nature story generators, pattern recognition machines, designed to tell what the world has done to them. Give us an incident, no matter how enigmatic, indeterminate, or tenuous its causes, and we will narrate in order to generate the hopeful, desperate impression of coherence. We are built to strong-arm links, invent causal chains that don’t exist. Give us a bedlam of stars and we’ll birth Sagittarius. This instinct is what Nassim Nicholas Taleb refers to as the narrative fallacy—that common intellectual blunder of forcing chaos into cosmos in an attempt to account for what eventuates around us and to us and through us.

Find the rest HERE.

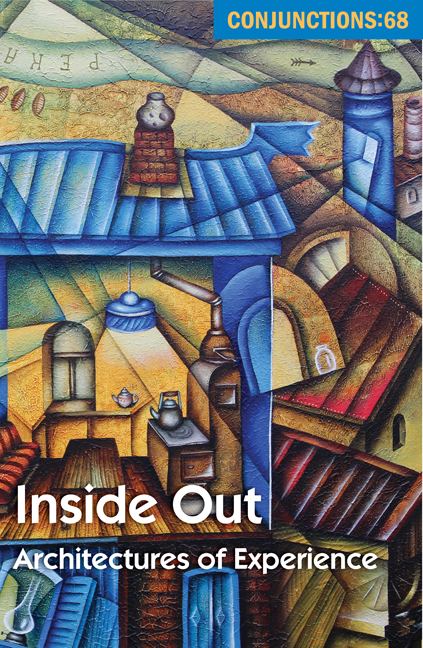

Happy to share that “The House That Jack Built,” a new fiction of mine, appears in Conjunctions:68, Inside Out: Architectures of Experience, alongside work by Robert Coover, Joyce Carol Oates, Lance Olsen, Nathaniel Mackey, Susan Daitch, Frederic Tuten, Joanna Scott, Andrew Mossin, Claude Simon, Louis Cancelmi, Cole Swensen, Robert Clark, Kathryn Davis, Elizabeth Robinson, Gabriel Blackwell, Monica Datta, Robert Kelly, Mary South, Brandon Hobson, Ryan Call, Ann Lauterbach, Can Xue, Karen Gernant, Chen Zeping, Matt Reeck, Lisa Horiuchi, Elaine Equi, G. C. Waldrep, Lawrence Lenhart, Mark Irwin, Justin Noga, Karen Hays, and Karen Heuler.

Happy to share that “The House That Jack Built,” a new fiction of mine, appears in Conjunctions:68, Inside Out: Architectures of Experience, alongside work by Robert Coover, Joyce Carol Oates, Lance Olsen, Nathaniel Mackey, Susan Daitch, Frederic Tuten, Joanna Scott, Andrew Mossin, Claude Simon, Louis Cancelmi, Cole Swensen, Robert Clark, Kathryn Davis, Elizabeth Robinson, Gabriel Blackwell, Monica Datta, Robert Kelly, Mary South, Brandon Hobson, Ryan Call, Ann Lauterbach, Can Xue, Karen Gernant, Chen Zeping, Matt Reeck, Lisa Horiuchi, Elaine Equi, G. C. Waldrep, Lawrence Lenhart, Mark Irwin, Justin Noga, Karen Hays, and Karen Heuler.