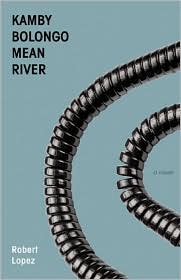

Check out my review of Robert Lopez‘s Kamby Bolongo Mean River. Here’s an excerpt:

Check out my review of Robert Lopez‘s Kamby Bolongo Mean River. Here’s an excerpt:

The absence of commas, colons, semicolons—actually all punctuation save the period, hyphen, and apostrophe—in Lopez’s novel makes for an oddball kind of rhythm where thoughts collide and then are abruptly stopped only to start again, like turning on a faucet and then quickly shutting off the valve, only to let it spurt out again. Ordinarily, Lopez’s constraints would result in suffocating prose, but instead, this dispensing of most punctuation, this stripping away of any inflection and any remotely flowery description, results in sentences that precisely limn the narrator’s consciousness, a narrator who would, given a chance, “rewrite the dictionary” because “[t]here are a lot of words in there [he doesn’t] like the definitions for.”